The Living Intelligence of Hyaluronan (HA) in Fascia

I first became obsessed with hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan, or just "HA") when I was teaching embryology. There's something mesmerizing about how this slippery, electric gel orchestrates the shaping of a developing embryo. But the more I traced HA's role through development, the more I realized we'd been missing its profound importance in adult fascia.

When I discovered our work would be part of Carla Stecco's Special Issue "Fascial Anatomy and Histology: Advances in Molecular Biology" in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, I was thrilled (this research sits alongside cutting-edge explorations of fascia at the molecular scale). Shout out to my collaborator, Prof Suzanne Scarlata, for getting this paper across the line before Christmas.

I'll be honest: the paper is dense. It's a molecular sciences journal, after all. But I know the fascia research community shares my fascination with the science, and I wanted to offer you an accessible translation of what we discovered... something you can actually use in your movement practice.

The Bio-Electric Gel

Let me start with what HA actually is, because it's far stranger and more elegant than most people realize. HA is an ancient polysaccharide (=many sugars). These sugar chains have been conserved across evolution from bacteria to humans, which tells you immediately that nature found something worth keeping.

One aspect of its extraordinary character arc is its water affinity. Not 1000 times its weight, though.

This molecule creates a hydrated gel matrix that fills the spaces in your fascia, but it's not just passive padding. The chains not only love water; they love calcium ions (Ca²⁺), and this is where things get truly electric.

Here's what blew my mind when I really understood it: Ca²⁺ are essentially the electric currency of your body. They're positively charged particles that cells use as their primary signaling system. When your heart beats, when your muscles contract, when your neurons fire... Ca²⁺ are the messengers carrying those electrical instructions.

And HA? It's negatively charged. Those carboxylate groups studding the HA chain are like tiny magnets with a negative pole, and they're irresistibly attracted to the positive charge of Ca²⁺.

So HA isn't just lube; it is an electrochemical communication system. When Ca²⁺ bind to HA's negatively charged sites, they can form bridges to other molecules like proteins and phospholipids, creating dynamic connections that affect everything from how smoothly your tissues glide past each other to how minerals crystallize during tissue repair.

In your joints, these Ca²⁺-HA (CHA) interactions modulate lubrication performance. Elevated calcium levels can actually reduce HA hydration, which is part of what happens in osteoarthritis. In bone formation, HA enhances Ca²⁺ binding to collagen, increasing local supersaturation and accelerating the crystallization of hydroxyapatite, the mineral that makes bone hard.

What makes this relationship so responsive is that it's based on electrical charges that can form and break in milliseconds. HA solutions exhibit rapid dynamic responses to stress partly because of these ionic interactions—the Ca²⁺ can quickly redistribute, the bridges can form and dissolve, the whole system can (and does) reconfigure itself almost instantaneously based on mechanical demands.

Here's the analogy that works for me: HA is like a smart suspension system in a high-performance vehicle that automatically adjusts based on road conditions. When you're cruising smoothly, it maintains optimal glide. When you hit rough terrain, it responds by producing more cushioning exactly where you need it.

Except unlike any human-engineered system, this one operates at the molecular level through electrical charges, responding to mechanical forces in real-time, and it's happening throughout your entire fascial network right now as you read this.

The gel isn't just sitting there—it's actively responding to every movement you make, every reach, every compression. It's viscoelastic, meaning it behaves differently depending on how fast and how much force you apply. And critically, it's a signaling molecule that talks to your cells, telling them what's happening in the mechanical environment and what they need to do about it.

The Discovery: A Feedback Loop We Didn't Know Existed

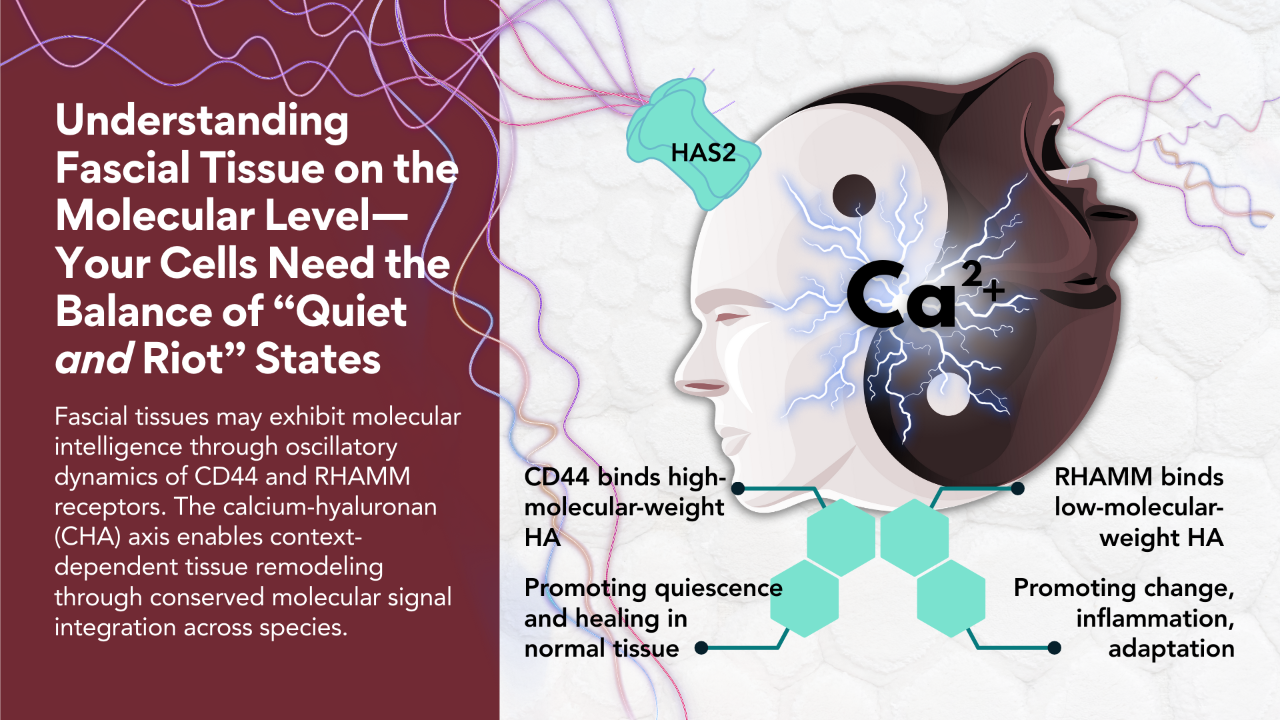

The core finding of our paper is what we call the CHA axis—the Calcium-Hyaluronic Acid axis—and it represents a complete feedback loop that I believe fundamentally changes how we should think about fascia and movement.

Here's the elegant part: mechanical forces trigger calcium signals inside fascial cells, which activate the production of HA, which improves tissue gliding, which allows for more movement, which generates more mechanical forces. It's a self-reinforcing cycle, a biological positive feedback loop that maintains fascial health through movement itself.

Think of it like a self-lubricating bearing, much as I know we're trying to get away from mechanics metaphors. With activity, friction generates a signal that triggers the production of more lubricant exactly where it's needed. But instead of friction being the problem, in fascia, mechanical loading is the solution. Your tissues have literally evolved in response to movement by fostering the conditions for better movement. Movement is our native input signal.

This isn't happening occasionally or only during injury repair. This is constant, dynamic, responsive. Every time you move, you're initiating this cascade. The fibroblasts in your fascia (and the cells we now call fasciacytes to recognize their specialized HA-extruding nature) are continuously sensing mechanical input and adjusting HA production accordingly [1,2,3].

What struck me most when I pieced this together was the realization that fascia isn't just responding to movement—it's in conversation with movement. The tissue is listening, interpreting, and answering back in the language of molecular biology. But you probably already knew most of this? What you may not have realized is coming next. And I'd love to hear how this is landing for you in the comments.

How Your Fascia Listens to Movement

So how exactly does fascia "hear" movement? The answer lies in specialized proteins embedded in cell membranes called mechanosensitive channels. I think of them as biological touch screens... they respond directly to physical deformation.

There are three main players: Piezo1, TRPV4, and TRPC5. Each one responds to slightly different mechanical signatures. Piezo1 is exquisitely sensitive to membrane stretch. When tissue is tractioned, Piezo1 channels open. TRPV4 responds to both stretch and changes in cell volume, like what happens during compression. TRPC5 is activated by membrane stretch but also integrates signals from other pathways.

When these channels open, Ca²⁺ rush into the cell. This isn't a simple on-off switch; it's more like a dimmer with infinite gradations. The amount of Ca²⁺ that enters, how quickly it enters, and how long the signal lasts all encode different information about the mechanical stimulus.

A quick, sharp stretch creates a different calcium signature than a slow, sustained load. Rhythmic, oscillating forces create calcium waves that look completely different from static compression. Your fascial cells can distinguish between these patterns, and they respond differently to each one.

This is why the quality of movement matters so much. It's not just about moving versus not moving. It's about the specific mechanical language you're speaking to your tissues. Different movement vocabularies create different calcium dialects, which trigger different cellular responses.

The Molecular Relay Race

Once Ca²⁺ enters the cell, it sets off a cascade that's like a relay race where each runner amplifies the signal before passing it on. This is where the molecular biology gets beautiful, like the sound of an orchestra in an ancient acoustic hall.

First, Ca²⁺ activates an enzyme called CaMKII (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II). Think of CaMKII (pronounced "Cam-Kay-Two) as part of the first responder team: it's fast, it's sensitive, and it kicks off everything else. CaMKII then activates PKC (protein kinase C), which activates the MAPK pathway (mitogen-activated protein kinases, particularly ERK1/2), which finally activates a transcription factor called CREB. This is how the calcium influx is amplified, resonating through cells and tissues.

Each step in this relay amplifies the signal. One Ca²⁺ can activate multiple CaMKII molecules. Each CaMKII is like a weighted flywheel that gets spun by the calcium influx, activating multiple PKC molecules. The amplification is exponential, which means a relatively modest mechanical stimulus can generate a robust cellular response.

CREB is the finish line of this relay; it enters the cell nucleus and binds to DNA, specifically turning on the gene for HAS2, one of the enzymes (there's also HAS1 and HAS3) that synthesize HA. This is the moment when mechanical force becomes genetic activation, when movement becomes molecular instruction.

But here's what makes this system so global: HAS2 doesn't just make HA inside the cell. It's embedded in the cell membrane, and it extrudes HA directly into the extracellular space as it synthesizes it, like a 3D printer building structure in real-time. The HA chains grow outward from the cell surface, immediately integrating into the surrounding fascial matrix.

This entire cascade—from mechanical stimulus to HA production—happens within hours. Your fascia is that responsive. Still with me? Heard this before? The quiet riot is coming...

Molecular Weight Matters: Two Different Messages

Not all HA is created equal, and this is where the fascia research and movement community is getting the upgrade. We're standing on the shoulders of the cancer research community here. The length of HA chains (what scientists call molecular weight) completely changes the message the molecule carries.

High molecular weight HA (HMW-HA) consists of long, intact chains. Think long, slinky, bioelectric, sugary loops of bioelectric gel pearls. When these long chains bind to a receptor called CD44 on cell surfaces, they send a calming, stabilizing signal. The message is essentially: "Everything's good here. Maintain homeostasis. Optimize gliding. Stay healthy." HMW-HA is anti-inflammatory, promotes tissue organization, and supports smooth fascial glide [9,12].

Low molecular weight HA (LMW-HA) consists of short fragments—broken pieces of what used to be long chains. These fragments bind to a different receptor called RHAMM (Receptor for Hyaluronan-Mediated Motility), and they send an alert signal. The message is: "Damage detected. Initiate repair. Remodel tissue. Recruit immune cells." LMW-HA is pro-inflammatory and activating—it mobilizes the cellular machinery needed for tissue repair.

This is the brilliance of being an Earthling biped. Your fascia uses the same molecule to send opposite messages depending on its structural state. Intact HA means healthy tissue. Fragmented HA means tissue that needs attention.

The balance between HMW and LMW HA determines whether your fascia is in maintenance mode (Quiet) or repair mode (Riot). Chronic inflammation, repetitive injury, and aging all shift the balance toward LMW-HA, which can create a persistent state of tissue activation that feels like stiffness, sensitivity, or pain.

Understanding this helps explain why movement quality matters so much. The right kinds of mechanical stimulation promote HMW-HA production and maintain the healthy, gliding state. The wrong kinds—or the absence of movement—allow HA to fragment and degrade, shifting tissue toward a reactive, inflammatory state.

Why This Matters for Your Movement Practice

But here's where I need to pump the brakes on my own enthusiasm and acknowledge something important: it's tempting to reduce this to a simple formula—"good movement = HMW-HA = healthy tissue" and "bad movement = LMW-HA = problem." The reality is far more nuanced, and honestly, more fascinating.

CD44 and RHAMM don't function as simple on/off switches. They have context-dependent, dual roles that we're still working to fully understand. CD44, for instance, plays crucial roles in wound healing, tissue regeneration, and healthy adaptation to mechanical stress. But when dysregulated, that same receptor can be implicated in pathological conditions like fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and even cancer progression. The receptor that helps coordinate beneficial tissue remodeling can, under different cellular conditions, contribute to excessive remodeling or persistent inflammatory states.

What determines when these systems shift from beneficial adaptation to pathological signaling? We don't fully know yet. It likely involves thresholds of mechanical stress, the biochemical environment of the tissue, the duration and pattern of signaling, and factors we haven't even identified. This is precisely why understanding mechanical thresholds and tissue context matters so much—and why there's still significant research needed in this area.

The complexity shouldn't discourage us. If anything, it should make us more curious and more thoughtful about how we approach movement and tissue health. Yes, movement matters profoundly. And yes, the system is more sophisticated than any simple formula can capture. That sophistication is what allows your fascia to respond intelligently to an infinite variety of mechanical situations... it's a feature, not a bug.

Everything I've just described isn't academic abstraction, although it involves the tinier end of the scale than most of us movers are normally comfrtable with. It's happening in your body right now, and it has direct implications for how you move, teach, and recover.

First, movement literally creates the conditions for healthy fascia. When you move, you're not just maintaining what's already there; you're actively triggering the production of the molecules that enable better movement. The CHA axis means that appropriate mechanical loading is therapeutic at the molecular level.

Second, the specificity matters. Different types of movement create different calcium signals, which trigger different cellular responses. This helps explain why varied movement—different speeds, different ranges, different qualities—supports tissue health better than repetitive, monotonous loading.

Third, this system needs time. The cascade from mechanical stimulus to HA production takes hours, and the remodeling of fascial tissue takes days to weeks. This is why consistency in movement practice matters more than intensity. You're training your tissues to maintain the molecular machinery for HA production.

Fourth, understanding the HMW versus LMW distinction helps explain recovery. After injury or during chronic pain states, tissues may be stuck in a LMW-HA, high-inflammation state. Gentle, progressive mechanical loading can help shift the balance back toward HMW-HA production and tissue homeostasis.

This is mechanobiology in action: your tissues are listening to mechanical input and responding with molecular precision. Every movement is a signal. Every load is information. Your fascia is reading the mechanical environment and adjusting its molecular composition accordingly.

Probably the worst thing you can do is be cowed into lack of movement for fear of doing it wrong. I'm going out on a limb here when I say that any movement is better than none.

The Elegant Intelligence of Fascia

The CHA axis reveals fascia as a responsive, adaptive, intelligent system. Mechanical forces trigger calcium signals, which activate HA synthesis, which improves tissue function, which enables more movement. It's a self-sustaining cycle that maintains tissue health through use.

I want to be clear: there's still much we don't know. The paper identifies significant research gaps, particularly around the specific mechanical thresholds that optimize this system and the need for more work specifically in fasciacytes rather than generic fibroblasts. We need better quantitative data on exactly how much force, applied how often, for how long, creates the optimal response. That work is ongoing.

But what we do know changes the conversation. Fascia isn't passive packaging. It's not just structural support. It's a mechanically responsive tissue system with its own molecular intelligence, constantly sensing and adapting to the mechanical environment you create through movement.

If you want the full molecular details—all the signaling pathways, the receptor dynamics, the feedback mechanisms—the complete paper is available here: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/27/1/160

For me, understanding these mechanisms deepens my appreciation for what's happening beneath the surface every time we move. Your fascia is listening. It's responding. It's adapting. And now we're beginning to understand the molecular conversation that makes it all possible.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join my mailing list and receive the latest on spiral motion, metabolism, and more.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

Your data is respected.